Deer physiological systems

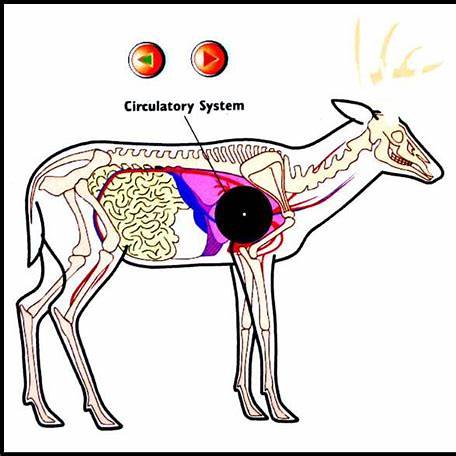

Circulatory System in deer

The circulatory system of the whitetail deer (Odocoileus virginianus) is similar to that of other mammals, designed to transport oxygen, nutrients, hormones, and waste products throughout the body. Below is an overview of its key components and features:

Heart

The heart is a four-chambered organ consisting of two atria and two ventricles.

It pumps oxygenated blood through the arteries and deoxygenated blood through the veins, maintaining circulation.

Blood Vessels

Arteries: Thick-walled vessels that carry oxygenated blood from the heart to the body.

Veins: Thinner-walled vessels that return deoxygenated blood from the body back to the heart.

Capillaries: Tiny vessels where the exchange of oxygen, carbon dioxide, nutrients, and waste occurs between the blood and tissues.

Blood

Whitetail deer blood contains red blood cells (for oxygen transport), white blood cells (for immune defense), platelets (for clotting), and plasma (the fluid component that carries nutrients and hormones).

Adaptations

Whitetail deer have specific adaptations in their circulatory system to support their active lifestyles:

- High Oxygen Delivery: Their circulatory system efficiently delivers oxygen to muscles during high-speed pursuits or long-distance movement.

- Thermoregulation: Blood flow to the extremities (e.g., ears, legs) can be adjusted to regulate body temperature. For example:

- Countercurrent Heat Exchange: Blood vessels in the legs and nasal passages are arranged to conserve heat in cold environments or dissipate heat in warm environments.

- Stress Response: During flight from predators, the heart rate and blood pressure increase dramatically to support a “fight-or-flight” response.

Unique Features

Seasonal Changes: The circulatory system adjusts to support metabolic changes during the rut (mating season) and in winter when their activity levels may decrease.

Antler Growth: During the growing season, antlers are richly supplied with blood through a network of vessels in the velvet covering. These vessels regress once the antlers harden and the velvet is shed.

The whitetail deer’s circulatory system is highly efficient, supporting its survival in various environments and activities like foraging, mating, and evading predators.

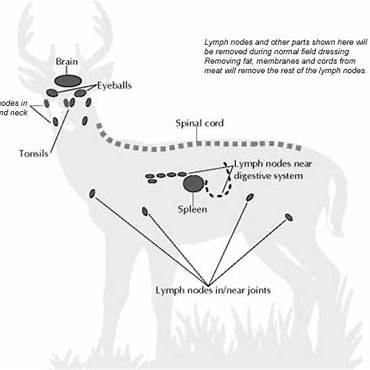

Lymphatic System in deer

The lymphatic system in whitetail deer (Odocoileus virginianus), like in other mammals, is an integral part of their immune and circulatory systems. It plays a vital role in protecting the animal from infections and diseases while maintaining fluid balance in the body.

Key Components of the Lymphatic System in Whitetail deer:

Lymphatic Vessels:

These vessels transport lymph fluid, which is rich in white blood cells (lymphocytes), proteins, and waste products.

Lymph vessels are distributed throughout the deer’s body, running alongside blood vessels.

Lymph Nodes:

Whitetail deer have lymph nodes scattered throughout their bodies, including prominent clusters in the neck, thoracic cavity, abdominal cavity, and near joints.

Lymph nodes filter pathogens, cellular debris, and foreign particles from the lymph fluid.

They are essential sites for immune responses, as they house lymphocytes and macrophages that detect and neutralize invaders.

Lymph Fluid:

A clear or slightly yellowish fluid that circulates through the lymphatic vessels.

It collects waste products, toxins, and pathogens from tissues and delivers them to the lymph nodes for processing.

Spleen:

The spleen is an important organ in the lymphatic system of deer, functioning to filter blood, recycle red blood cells, and produce lymphocytes.

Thymus:

The thymus, active in young deer, is where T lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) mature. This organ shrinks as the deer ages.

Functions of the Lymphatic System in Whitetail Deer:

Immune Defense:

Detects and responds to infections, parasites, and diseases like chronic wasting disease (CWD), a prion disease that specifically affects deer.

Fluid Regulation:

Helps maintain tissue fluid levels by collecting excess interstitial fluid and returning it to the bloodstream.

Fat Absorption:

In the digestive system, lymphatic vessels (lacteals) in the small intestine absorb fats and transport them to the circulatory system.

Diseases Affecting the Lymphatic System:

Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD):

Affects lymphoid tissues, especially in the early stages. Prions accumulate in the lymph nodes and spleen before spreading to the nervous system.

Parasitic Infections:

Internal parasites like lungworms and liver flukes may impact the lymphatic system by causing localized inflammation or blockage.

Bacterial Infections:

Conditions such as abscesses can involve nearby lymph nodes, leading to swelling and tenderness.

Understanding the lymphatic system of whitetail deer is crucial for wildlife biologists, veterinarians, and conservationists, particularly in monitoring diseases like CWD and their impact on deer populations.

Whitetail Deer Glands

Whitetail deer have various glands throughout their bodies that serve critical roles in communication, territory marking, and mating behavior. Here’s an overview of their primary glands and their functions:

Preorbital Glands

Location: Just below the eyes.

Function: These glands produce a secretion used to mark vegetation. Deer rub these glands on twigs or branches to communicate presence and establish dominance.

Forehead Glands

Location: On the forehead, especially prominent in males.

Function: Active in bucks, especially during the rut. The scent is transferred to branches or antlers during rubs and scrapes, signaling dominance or territoriality.

Tarsal Glands

Location: Inside the hind legs, at the hock joint.

Function: Key in social communication, especially during the rut. Deer urinate over these glands (a process called “rub-urination”) to create a unique scent that signals identity, dominance, and reproductive status.

Metatarsal Glands

Location: Outside the lower hind legs, just above the hooves.

Function: Thought to play a role in environmental awareness, these glands may emit scents related to stress or alert others to danger.

Interdigital Glands

Location: Between the hooves of all four feet.

Function: Secrete a waxy substance used to leave a scent trail as the deer walks, aiding in communication and navigation.

Nasal Glands

Location: Inside the nostrils.

Function: Help keep the nose moist, aiding in scent detection, which is critical for finding food, detecting predators, and social interaction.

Sebaceous (Skin) Glands

Location: Distributed across the skin.

Function: Secrete oils to maintain skin health and fur condition, and they might contribute to general scent marking.

Understanding these glands gives insight into the complex communication system of whitetail deer, especially during the breeding season and territorial disputes.

Whitetail Deer Reproduction

White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) have a reproductive system adapted for seasonal breeding, which allows them to produce offspring at optimal times of the year. Here’s a general overview of their reproductive organs:

Male Reproductive System (Buck)

Testes: Located in the scrotum, which is external to the body to maintain a temperature conducive to sperm production. Testosterone production and sperm development occur here.

Epididymis: A structure adjacent to the testes where sperm matures and is stored.

Vas Deferens: Transports sperm from the epididymis to the urethra during ejaculation.

Accessory Glands: These produce seminal fluid to help transport and nourish sperm.

Penis: The organ responsible for delivering sperm into the female reproductive tract during mating.

Female Reproductive System (Doe)

Ovaries: Produce eggs (ova) and release hormones like estrogen and progesterone, which regulate the reproductive cycle.

Oviducts (Fallopian Tubes): Fertilization occurs here when sperm meets an egg.

Uterus: Provides the environment for embryonic and fetal development. A bicornuate uterus with two uterine horns accommodates the development of multiple offspring.

Cervix: A muscular structure that acts as a barrier to the uterus, allowing sperm entry during mating and protecting the developing fetus during pregnancy.

Vagina: The passage through which the male deposits sperm during mating. It also serves as the birth canal during delivery.

Reproductive Cycle

Estrous Cycle: Female deer come into heat (estrus) during the breeding season, which is typically in the fall. Estrus lasts about 24-48 hours and recurs every 21-29 days if the doe is not impregnated.

Mating: Bucks compete for access to does during the rut, which coincides with the females’ estrus cycles. Successful mating leads to fertilization in the oviducts.

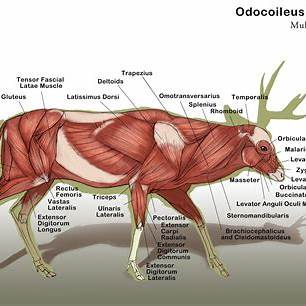

Musculatory System in deer

The musculatory system of a whitetail deer is a complex network of muscles that enables the animal’s movement, strength, and agility, which are essential for survival in the wild. This system is highly specialized to support the deer’s lifestyle, including sprinting, leaping, and navigating various terrains. Below is an overview of the key muscle groups and their functions:

Neck Muscles

Primary Muscles: Sternocephalicus, splenius, and longus colli.

Functions:

Support the head and allow movement such as turning, raising, and lowering.

Crucial for grazing and alert behavior.

Shoulder and Forelimb Muscles

Primary Muscles: Trapezius, deltoid, biceps brachii, triceps brachii, and infraspinatus.

Functions:

Provide strength and flexibility for running and leaping.

Allow forward and lateral movement of the forelimbs.

Back and Core Muscles

Primary Muscles: Longissimus dorsi, latissimus dorsi, and psoas major.

Functions:

Stabilize the spine during rapid movements.

Provide support for the body during leaping or climbing.

Hindquarters

Primary Muscles: Gluteals, semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and biceps femoris.

Functions:

Powerhouse for propulsion and speed.

Enable explosive movements such as bounding and jumping.

Abdominal Muscles

Primary Muscles: External oblique, internal oblique, and rectus abdominis.

Functions:

Support internal organs.

Aid in respiration and maintaining posture.

Leg Muscles

Primary Muscles: Quadriceps, gastrocnemius, soleus, and digital flexors.

Functions:

Facilitate walking, running, and maintaining balance.

Absorb shock during landing after jumps.

Adaptations for Survival

Whitetail deer are known for their agility and speed, with muscle fibers adapted for short bursts of high energy:

Type I (Slow-twitch fibers): Support endurance for sustained movement.

Type II (Fast-twitch fibers): Enable quick acceleration and escape from predators.

Conclusion

The musculatory system of a whitetail deer is optimized for strength, speed, and versatility, ensuring that these animals can navigate their environments efficiently while evading predators. This system is a remarkable example of adaptation in mammals.

Digestive System in deer

The digestive system of a whitetail deer is highly specialized and adapted to process a diet of fibrous plant material efficiently. It is a ruminant digestive system, similar to that of cattle and sheep. Here’s an overview:

Key Components of the Digestive System

Mouth and Teeth:

Whitetail deer have specialized teeth for browsing and grazing. Their incisors cut vegetation, and the molars grind plant material to begin the digestive process.

Saliva contains enzymes that help break down food and facilitate swallowing.

Esophagus:

Transfers food to the stomach through muscular contractions.

Four-Chambered Stomach:

Rumen:

The largest chamber, where fermentation occurs.

Microorganisms (bacteria, protozoa, and fungi) break down cellulose in plant cell walls into volatile fatty acids, which are absorbed as a primary energy source.

Food is regurgitated from the rumen as “cud,” chewed again, and swallowed to further break it down.

Reticulum:

Works closely with the rumen.

Filters smaller food particles and traps foreign objects (like ingested debris).

Fermentation continues here.

Omasum:

Absorbs water and nutrients from the digested material.

Acts as a filter to allow only fine particles to pass to the next chamber.

Abomasum:

The “true stomach,” functioning similarly to a monogastric (single-chambered) stomach.

Produces gastric juices to digest proteins and kill microorganisms from the rumen, making them available as additional nutrients.

Small Intestine:

Enzymes and bile further break down food particles.

Nutrients such as amino acids, sugars, and fatty acids are absorbed.

Cecum:

Located at the junction of the small and large intestines.

Contains microorganisms for additional fermentation, particularly for fibrous plant material.

Large Intestine:

Absorbs water and remaining nutrients.

Forms feces for elimination.

Rectum and Anus:

Waste material is expelled from the body as pellets.

Adaptations

Selective Feeding: Deer prefer high-quality forage (e.g., tender shoots, leaves, and acorns) to maximize nutrient intake.

Seasonal Variation: Their diet and digestive efficiency adjust with the seasons to adapt to available food sources.

Efficient Fermentation: Microbial populations in the rumen can adapt to different types of plant material, ensuring effective digestion of their diet.

This system allows whitetail deer to thrive in diverse habitats by efficiently extracting nutrients from fibrous and often nutrient-poor food sources.